In many contemporary scenarios wherein a designer is working with new media, there is usually a requirement for an emphasis on user interactivity, user input, and repeat-use – as is often seen in application, interface, system, or website development – which is known as user experience and user interface design. User experience and user interface design, or UX and UI for short, may be difficult for some designers with experience only in static design (print advertising, magazine layout, and pagination design); however, by examining other fields that successfully employ UX/UI design, such as system and videogame design, designers can identify the following successful principles of UX/UI design (Kendrick):

- The user should not have to stop and think about how to do something.

- The interaction between the user and the medium should be natural and intuitive.

- The user/interface operations must be consistent throughout all areas of the UX/UI.

The field of UX/UI design has been around since the late 1940s C.E. in regards to human factors and ergonomics, which focuses on the interaction between human users, machines, and environments. There are many key factors to understanding UI and how it can enable a favorable UX, but most are centered on principles such as defining interaction patterns, incorporating user needs, featuring information that is important to the user, and making the interface intuitive by building behaviors like drag-and-drop, selections, mouse-over actions, buttons, and so on. Although many techniques can be employed to provide a positive UX, most of these principles primarily focus on the UI utilizing remediation to foster user accessibility, interaction, and familiarity.

The word remediation is derived from the Latin remederi – ‘to heal, to restore to health,’ and the English ‘the action of remedying something, in particular of reversing or stopping environmental damage’; however, for the purposes of this paper remediation is a design concept that refers to when an aspect of an older media is somehow present in a newer media, and it exists aesthetically, culturally, and experientially in different forms of media and technology. A popular example of remediation can be seen in the first personal computer, which was an entirely new invention, but imitated or mimicked the typewriter and television. So, in this instance both the typewriter and the television where ‘remediated’ in the personal computer as a monitor and keyboard.

Paul Levinson uses the term ‘remediation’ to “describe how one medium reforms another… (to) improve on the limits of prior media” (Levinson 105-114); Levinson’s use and definition of the term ‘remediation’ is important to the understanding of the evolution and contemporary meaning of the Graphic Design term. In the book Remediation: Understanding New Media David Bolter and Richard Grusin define remediation as “to express the way in which one medium is seen by our culture as reforming or improving upon another… (and) repurposing earlier media into digital forms” (59). Bolter and Grusin further describe this meaning by using the metaphors of broadcast television becoming interactive digital television, electronic mail being more convenient and reliable than physical mail, the novel being replaced with digital hypertext, and virtual reality as being perceived more ‘natural’ of an environment than a conventional video screen (when it comes to computing).

Furthermore, and as it relates specifically to new media and design, Meredith Davis states that remediation is “the process through which the characteristics and approaches of competing media are imitated, altered, and critiqued in a new medium… (or) the representation of one medium in another” (Davis 213). When considering remediation as it pertains to design, the use of remediation in UX/UI design can not only help achieve successful design results for the user, but can also be a valuable tool in a Graphic Designer’s skillset. So, when looking at specific fields that utilize remediation in UX/UI design, the field of indie videogame production relies heavily on remediation through its subtle incorporation of media imitation, its utilization of media referencing, and its use of media criticism.

To explain further, in the field of videogame production, there exits both platform publishers and inde videogame developers, and the significant difference between these two publishers is almost wholly defined by their titles, publishers and developers. Inde videogames are created by individuals or small teams, generally without big videogame publisher financial support (Microsoft, Nintendo, Sony, etc.), while focusing on innovation and relying on digital distribution. Videogame publishers are primarily concerned with profit margin, related product sales (action figures, movies, clothing, etc.), micro-transactions, and profitably of videogame sequels; in contrast, idie videogame development is almost seen as being more human and sincere. This is best embodied in the 2012 film Indie Game: The Movie, where the indie game developer Edmund McMillen states, “my whole career has been me, trying to find new ways to communicate with people, because I desperately want to communicate with people” (Pajot and Swirsky).

UX + Aesthetic Remediation

One of the most prevalent and excellent examples of remediation in indie videogames is the incorporation of UX/UI media imitation, which can be seen through remediated aesthetics and interfaces. If one were to examine the major platform console videogame systems right now (Play Station 4, X-Box One, etc.),they all have Blu-ray/DVD, Game DVR (digital video recorder), 8GB RAM (8 gigabytes of random access memory), HDMI (high-definition multimedia interface) input and output, and 8 core central processing units (IGN). Suffice to say, the graphic capabilities of contemporary videogame systems are astounding, an example of which can see by looking at Electronic Arts’ Crysis 3 (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Videogame screenshot; “Crysis 3”; http://www.crysis.com/crysis-3, 16 Apr. 2013; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

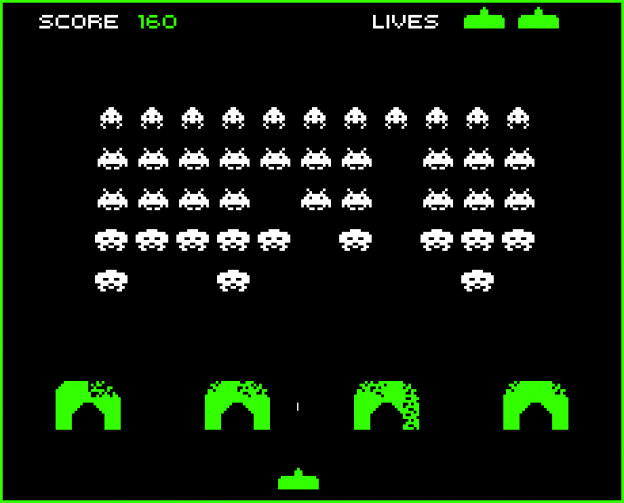

Having stated the previous, if one looks at the 1978 C.E. video game Space Invaders (see fig.2) – an arcade videogame designed by Tomohiro Nishikado that was one of the earliest shooting games and a forerunner of modern videogaming – the videogame only had a display resolution of 217 by 248 pixels, which reflected the display capabilities of the arcade screen at that time.

Fig. 2. Arcade game screenshot; “Space Invaders”; http://en.wikipedia.org/, 29 May 2008; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

Now, most videogames are produced for a 1920 by 1080 pixel display screen, even indie videogames, which affords the potential of high-definition videogame imagery, or graphics; however indie videogames employ a UI design aesthetic known as ‘retro style gaming’, which is an example of remediating an older video game aesthetics, and provides a UI that is already familiar to the typical videogame user.

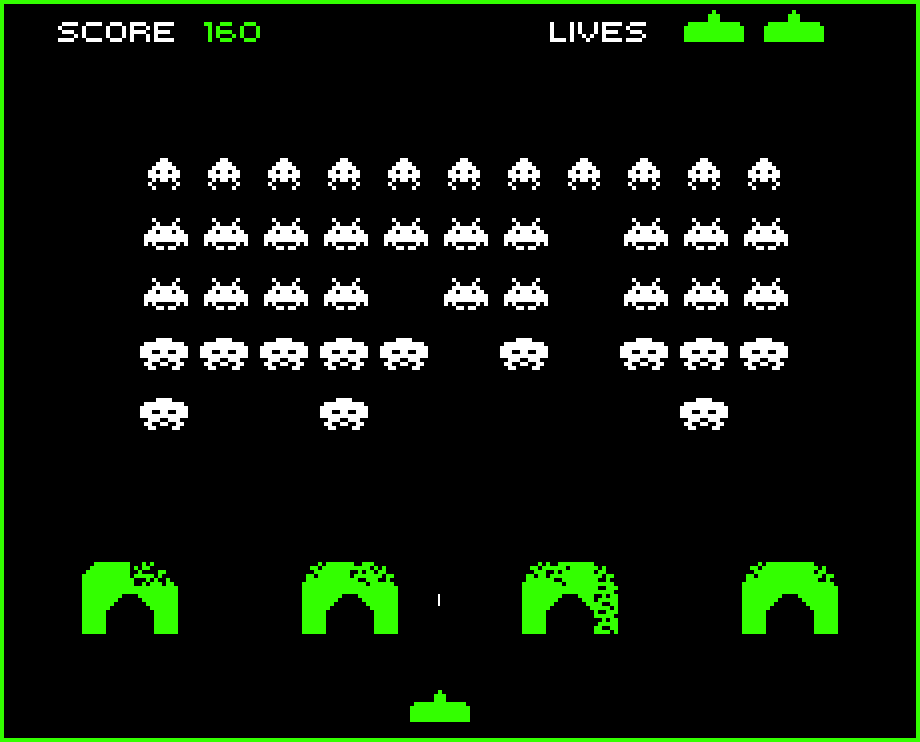

The indie videogame BIT.TRIP BEAT is an arcade-style music video game developed by Gaijin Games, and released in 2009 through 2010 C.E. (see fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Arcade game screenshot; “BIT.TRIP BEAT”; http://www.mobygames.com/, 6 Mar. 2011; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

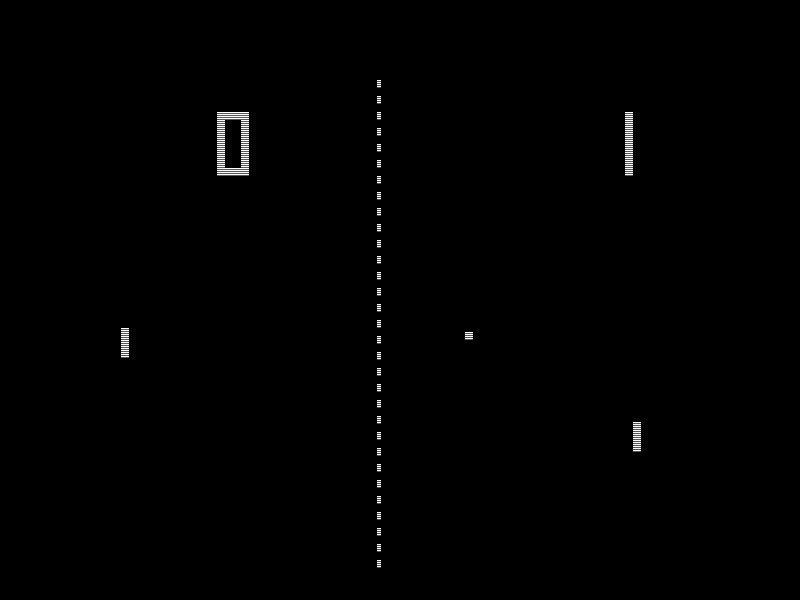

BIT.TRIP BEAT puts players in control of a paddle that deflects musical beats of size and color – very much like the UX in the 1972 C.E. videogame Pong (see fig. 4) – which remediates the pixelated graphics of the very first videogames of the 1970s C.E.

Fig. 4. Arcade game screenshot; “Pong”; http://en.wikipedia.org/, 21 May 2006; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

Additionally, as the ‘beats’ come from the right side of the screen they collide with the paddle, which makes a noise. As the player gets better completing the musical beats makes up a song, and the graphics of the game move from 8 bit, to 16 bit, to 32 bit graphics, thus rewarding UX through gameplay; however, as the player does poorly, so does the song break apart, and the graphic mode reverts back from 32 bit, to 16 bit, to 8 bit graphics (an example of this can be seen on the publisher AksysGames’ YouTube channel at http://youtu.be/r0Pl4sPurck).

Another example of indie videogames remediating pixelated graphics (and videogame soundtracks) of older videogames to create a familiar UX can be seen in the 2012 indie videogame Mutant Mudds, which was developed and published by Renegade Kid. If one looks at a closer at the graphics of the video game (see fig. 5) they can see that the characters and enemies have an overly-exaggerated use of pixels, as opposed to the background on which the videogame is played.

Fig. 5. Arcade game screenshot; “Mutant Mudds”; http://www.ign.com/, 10 Jan. 2013; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

This remediation in the UI, and ultimately UX design, is done to both imitate and reference media examples in older videogames, and although Mutant Mudds is a videogame that was released in 2012, it references the videogaming style of Capcom’s 1978 C.E. Mega Man. The soundtrack and videogame play comparison can be seen by watching http://youtu.be/ECgh-RDsVn0 and http://youtu.be/99xFEm-4I1I.

UI + Input Remediation

An additional example of remediation in indie videogames, and the incorporation of media imitation, can be seen in videogame input interfaces and UI design. For example, the typewriter or ‘QWERTY’ keyboard was first invented for the Sholes and Glidden typewriter and sold to Remington in 1873 C.E. Additionally, the a ‘touch tone’ telephone keypad as standardized when the dual-tone multi-frequency system in the push-button telephone was introduced in the 1960s C.E. An example of this can be seen in the Western Electric telephone (see fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Photograph; “Push Button Western Electric Princess Telephone”; http://www.etsy.com/, 19 Feb. 2013; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

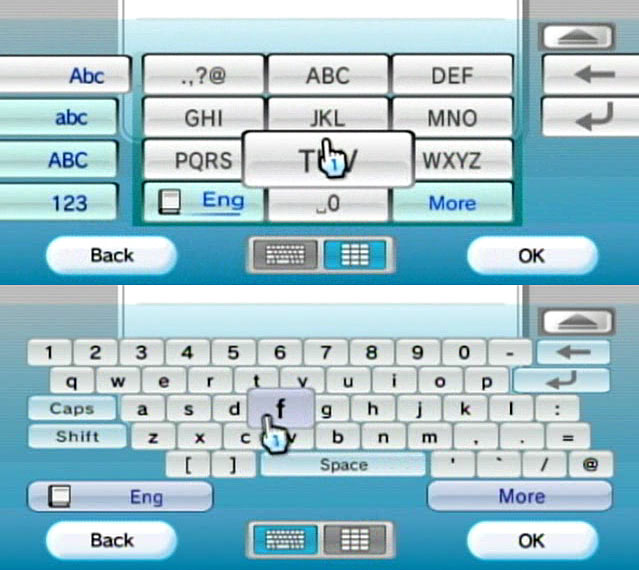

Both of these input interfaces from the 1870s and the 1960s C.E. are remediated as UI design elements not just in many indie videogame interfaces, but also in videogame console UI design, which constitutes a perfect example of remediation in videogames (see fig. 7), and affords the user an ease of use, without a required learning curve.

Fig. 7. Screen collage; “Nintendo Wii interface”; http://www.ryansgoblog.com/, 28 Oct. 2008; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

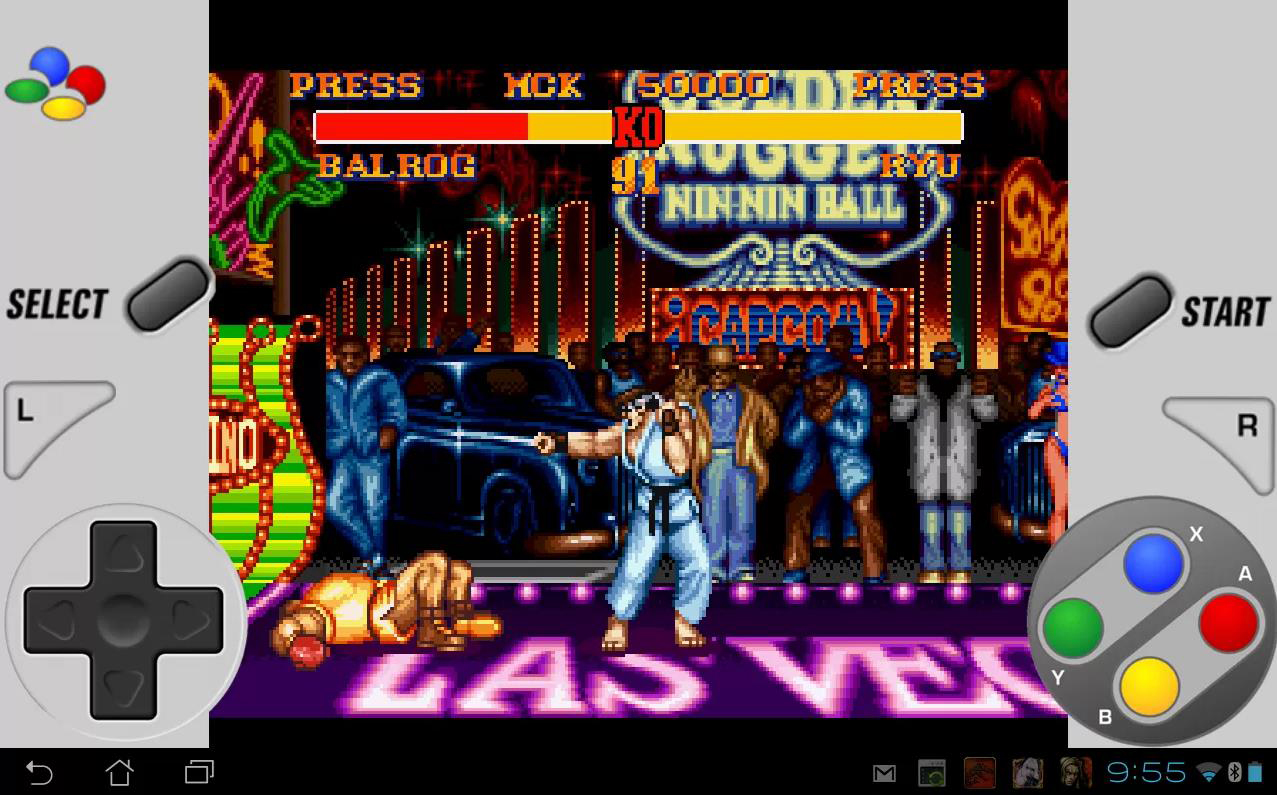

Also, when older videogames are no longer available – which is referred to as videogame moratorium – those games are often available for emulation on computers or smartphone devices. When emulation is an option on a smartphone, often times the existing UI design isn’t similar to the original videogame controller, so the app developers design a UI and create a remediated game controller to allow the user to play the videogame. An example of this can be seen in the 2012 C.E. Android smartphone app SuperGNES ‘s UI design (see fig. 8), which remediates the 1991 C.E. Nintendo’s SuperNES videogame controller UI design (see fig. 9).

Fig. 8. Android smartphone screenshot; “SuperGNES Street Fighter II”; https://play.google.com/, 19 Jun. 2013; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

Fig. 9. Photograph; “Super NES; http://en.wikipedia.org/, 14 Feb. 2011; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

Aesthetic + Input Remediation = Successful UX/UI Design

Another prevalent example of remediation in UX/UI design can be seen in the type of videogame or gameplay referencing the media of another game in the context of the new videogame. Examples of this in indie videogames can be seen in a videogame’s UI design, and the UX of the videogame’s world. The first example that demonstrates this is text-based adventure games.

In 1979 C.E. Ken and Roberta Williams released Mystery House (see fig. 10), the first text adventure game which featured vector graphics of each environment alongside a two-word parser.

Fig. 10. Videogame screenshot; “Mystery House”; http://en.wikipedia.org/, 7 Dec. 2005; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

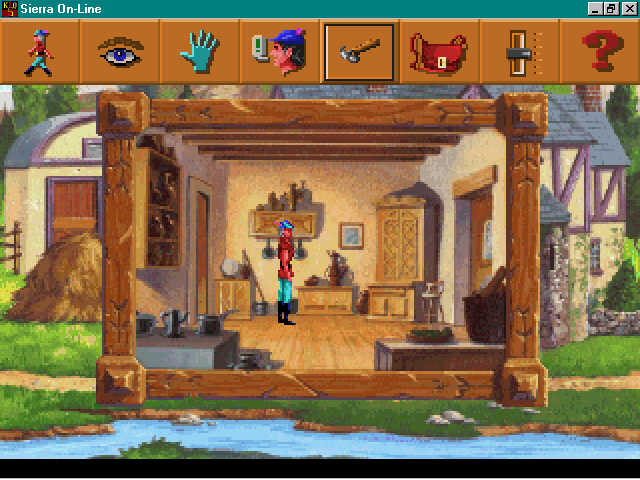

Mystery House did so well that in 1980 C.E. the both Ken and Roberta Williams founded Sierra On-Line. Soon after, Sierra On-Line had launched multiple successful series of adventure games, and these games functioned by UI that were still entered on the keyboard, and analyzed by a syntax interpreter. Such game series included King’s Quest (see fig. 11), Police Quest, Space Quest, and Hero’s Quest.

Fig. 11. Videogame screenshot; “King’s Quest”; http://en.wikipedia.org/, 26 Jul. 2005; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

A few years after these series had started the classic keyboard-based commands were replaced with the UI design of ‘point-and-click’ mouse-based gameplay. One of the first examples of this was the 1995 C.E. videogame King’s Quest 5: Absence Makes the Heart Go Yonder, wherein one can see a UI design of a mouse-based toolbar that allowed the UX of choosing options that would allow their character to start walking, looking, performing an action or speaking (see fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Videogame screenshot; “King’s Quest V”; http://static.giantbomb.com/, Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

A remediation of this mouse-based UX/UI design can be seen in the 2009 C.E. indie videogame Tales of Monkey Island, almost fifteen years later. Tales of Monkey Island (see fig. 13) is also a graphic adventure video game developed by Telltale Games and LucasArts, but was developed for Nintendo Wii console, and featured an immersive UX with a 3D animated world, full character animation, full audio soundtrack, and full audio dialog of all characters in the videogame (http://youtu.be/rygOaL2zjng to see the point-and-click mouse-based gameplay in action).

Fig. 13. Videogame screenshot; “Tales of Money Island”; http://www.gogaminggiant.com/, Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

The use of this familiar and intuitive UI allows the user to not have to stop and think, but rather jump right in and start creating and enjoying a great UX (Kendrick).

Another example of great UX/UI design through a videogame’s world that is remediated can be seen in the 2012 MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing game) Guild Wars 2 (see fig. 14), which permanently implemented a ‘Super Adventure Box’ mini-world that is akin to the 1991 C.E. videogame Sonic the Hedgehog (see fig. 15).

Fig. 14. Videogame screenshot; “Guild Wars 2’s Super Adventure Box”; http://kotaku.com/, 31 Mar. 2013; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

Fig. 15. Videogame screenshot; “Sonic the Hedgehog”; http://www.slidetoplay.com/, 16 May 2013; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

According to Mike Fahey game writer for Kotaku, an internationally popular videogaming forum, ‘Super Adventure Box’ was “originally planned as a fake 8-bit update to celebrate April Fools’ Day… (but) grew into an expansive three-level homage to the golden age of gaming” (Fahey). This combination of a remediated aesthetic with a remediated UI, creates one of the most successful expansions for Guild Wars 2, providing a fantastic UX for thousands of players, and allowing them to enjoy a natural and intuitive interaction between the user and the medium (Kendrick).

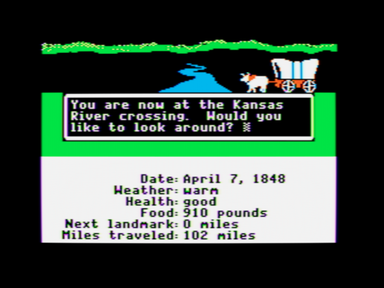

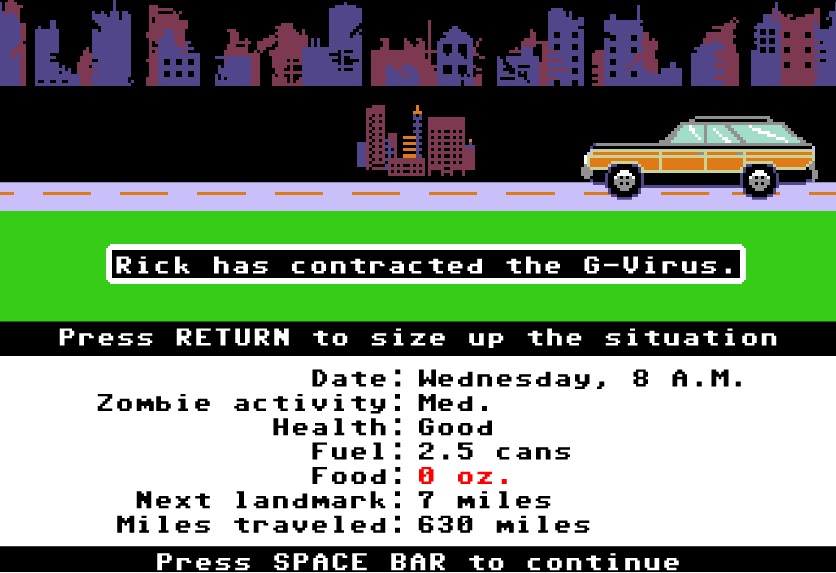

Finally, a lasting example of UX/UI design remediation in indie videogame development, wherein a newer media of videogame is critiquing or parodying an older videogame media, can be seen between the two examples of 1974 The Oregon Trail videogame, and the 2012 The Organ Trail videogame.

The Oregon Trail was a computer game originally developed by Don Rawitsch, Bill Heinemann, and Paul Dillenberger. The Oregon Trail was produced by the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium (MECC), and the UX was that of teaching about the realities of 19th century pioneer life on the actual Oregon Trail. In contrast, The Organ Trail is a retro zombie survival game in which players must cross a post-apocalyptic United States of America in an old station wagon (as opposed to a covered wagon) in order to reach a sanctuary free of zombies.

If one were to examine the screenshots of both videogames side-by-side, one would see how similar they are to each other. Obviously the The Organ Trail (see fig. 16) UI design parodies the edutainment game The Oregon Trail (see fig. 17), but this is an excellent example of UX/UI design remediation in indie videogames in regards to concept, graphics, and appropriation of user experience, which enhances the final design for the user, and equals user/interface operation that is consistent throughout all areas of the UX/UI .

Fig. 16. Videogame screenshot; “The Oregon Trail”; http://en.wikipedia.org/, 2 Aug. 2012; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

Fig. 17. Videogame screenshot; “The Organ Trail”; http://fatratgaming.com/, 29 Mar. 2013; Web; 30 Jul. 2013.

In Conclusion…

Remediation in UX/UI design is a very successful component of indie videogame development, which is apparent through its UI’s incorporation of media imitation and remediated input. The aesthetic, cultural, and experiential influences of remediation in indie videogames are very noticeable, are a valuable asset to the indie videogame developer, and offer a valid example of the potential UX/UI tool available to all designers.

So, when confronted with opportunities and problems in any design field – be it an application design, a website interface, or an interactive system – remediation can potentially be a useful tool to foster interactivity, input, and repeat-use for the user especially in UX/UI design. A designer should strive for user/interface consistency, natural and intuitive interaction, and enabling the user ‘to do’ rather than stopping them with a bad UI and an even worse UX design.

Resources:

Bolter, David J. and Grusin, Richard. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999. Print.

Davis, Meredith. Graphic Design in Context: Graphic Design Theory. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2012. Print.

Fahey, Mike. “This Fully-Playable 16-Bit Wonderland is Guild Wars 2‘s Idea of a Joke.” Kotaku, 31 Mar. 2013. Web. 30 Jul. 2013. (http://kotaku.com/this-fully-playable-16-bit-wonderland-is-guild-wars-2s-464761894)

Human Factors and Ergonomics Society. “About HFES.” HFES, 10 Aug. 2013. Web. 10 Aug. 2013. (https://www.hfes.org/)

IGN. “PS4 vs. Xbox One vs. Wii U Comparison Chart.” IGN Wiki. International Gaming Network, 30 Jul. 2013. Web. 30 Jul. 2013. (http://www.ign.com/wikis/xbox-one/PS4_vs._Xbox_One_vs._Wii_U_Comparison_Chart)

Indie Game: The Movie. Dir. Lisanne Pajot, James Swirsky. Perf. Jonathan Blow, Phil Fish, Edmund McMillen, Tommy Refenes. Sundance, 2012. Film.

Kendrick, James. “3 rules for a good user experience (UX).” ZDNet Mobile News. 9, Jul. 2013. (http://www.zdnet.com/3-rules-for-a-good-user-experience-ux-7000017818/)

Levinson, Paul. The Soft Edge: A Natural History and Future of the Information Revolution. New York: Routledge, 1997. Print.